Chapter 10

The next time Patrick visited Carmel at the hospital she told him that Nurse Mantell told her they had changed Carmel's name at the hospital to Tuite and Finbar's name to Esther Tuite – yes also his sex.

On the same evening that Carmel was admitted, a Mrs Mary Tuite was also admitted and she gave birth to a daughter called Esther. Mrs Tuite was discharged two days later so if anybody found out what name Carmel was using it would be too late.

The Reverend Wilde and his wife, Nora, showed up at the hospital later. The galoot of a preacher who saw Carmel arrive initially, called them on the phone and told them what name Carmel was under, i.e. O'Brien.

When the Wildes arrived, all the way in from the wilds of Dún Laoghaire, they asked where Mrs O'Brien was. They were told there was nobody there, with that name.

They met the galoot of a preacher who looked at the information in the hospital records, confirmed it, and also gave the Wildes the address where Mrs O'Brien resided; Theresa's address in Ballybough and the Christian name of the mother was Síle.

The office manager of the reception area told the President and Board of An Bord Altranais and its Chief Executive Officer what was happening and he, a Mr Fergus O'Toole – yer man with the pinz-nez spectacles – came and saw the Wildes. 'Youz two again: now what do they want?' he said.

'They're after someone called O'Brien.' said the office manager 'and I told them that nobody of that name is a patient here.'

The Chief Executive Officer, stretched himself to his full height of five feet six, settled the pinz-nez spectacles on the bridge of his nose and said, very clearly to the Wildes 'O'Brien!! is it? And what was it the last time?'

'Wilde.' said the reverend,

'Yes Wilde – where are you getting these names from – the head stones in Glasnevin Grave Yard?'

'No – we were told that . . . '

'Get on the other side of those doors before I call the Garda Síochána who will manfully – and woman fully if you will pardon me for saying so, Missus – THROW YIZ OUT!!'

'I demand that you let . . .'

'Get out!!!!' screamed the little fella as the pinz-nez spectacles, fell off his nose 'and take this mountebank with you' – referring to the galoot of a preacher 'and don't you' as he pointed again at the galoot of a preacher 'don't let me see you here again; you're banned, do you hear me, banned.'

They all scuttled out of the place.

Fergus O'Toole turned to the staff in the reception office and said 'I feel better for that!' and he walked back to his little office with a skip and a jump as the spectacles swayed to and frow as they hung from the cord on his chest.

When they got to the bottom of the steps outside the reverend said 'we know where they are – come on.'

And they headed off to Theresa's in Ballybough.

Annesley Avenue, on a sunny Sunday afternoon, was its usual busyness, which consisted of about fifteen to twenty men, the toss school, with their shirt sleeves rolled up, after two hours in McCann's pub, tossing coins into the air and shouting the odds and when they landed most of them shouted 'Oh God' or 'in the name of Jaysus' and just as the Wildes, with their lackey, the galoot of a preacher behind them, turned the corner into the avenue to a huge crescendo of the biggest bet of the afternoon in their ears, they heard the noise stop at the sight of two protestant priests in Ballybough.

The Wildes went to Theresa's door and before they knocked it the crowd shouted 'round the back.'

There she was, round the back, Theresa O'Brien with her skirt pulled up to reveal a fine pair of legs taking in the sun. when the unmistaken accent of Armagh permeated the air with 'Mrs O'Brien?'

Theresa looked up from her book. She knew who they were - Carmel's parents - and she said 'Agus cad é atá uait - tú féin agus do bhóna madraí?'

They didn't understand Irish and the reverend said 'I am after my daughter and my grandson and I believe, they are in there.'

'Cén fáth nach bhfuil tú ag breathnú?' said Theresa.

'I don't understand a word – answer me! Answer me in English.'

'Take a look' said Theresa 'but don't touch a thing.'

The Wildes, followed by their acolyte went towards the door 'Not you' said Theresa to the galoot.

An hour later the Garda pulled up at Theresa's front door on a motor bike and side car; one minute before this the men were in the street tossing: every doorway had young kids around twelve or so, playing cards, and when the word went up, the avenue was cleared before the Garda arrived.

Not a soul in the avenue.

A female officer, officially called banghardaí, got out of the side car and went to the front door. There was nobody to shout 'round the back' so she knocked.

Silence.

Over the street, net curtains were seen moving as if a breeze was blowing them. The banghardaí waited on the step and looked around. 'Try round the back, Mary' came from the rider of the motor bike at the kerb.

Mary went around the back to see Theresa reading the book.

'Howya Theresa?' said the cop.

Theresa looked up.

'O forgot you lived here.' said Mary.

'Am I ever going to finish this bleedn' scuttering book?' she said.

'What is it?' said Mary.

'I'm struggling my way through The Razors Edge, if you really want to know: getting really involved in this fine piece of literature and trying to figure out who was the alcoholic: who was married to whom and what, in the name of Jaysus, were they doing in India in the first place? And every time I sit down to read, some gob shite interrupts . . no offence, Mary, I don't mean you.'

She looked at the book. 'Will you give us a look at that when you're done.'

'I promised to somebody else' said Theresa 'Now: what do yiz want?'.

'We have to search your house?'

'What for? Is this something to do with the prod priest who was here a while ago?'

'We were told this morning to come and search the house but we had to get mass first?'

'Why?' said Theresa.

'I always go to mass on Sundays.'

'No not that – why are you wanting to search the house?'

'I'm not supposed to say.'

'I know that.' said Theresa 'but why?'

'I don't know why but we're – we're looking for blood.'

'Blood!! Real blood?'

'Yes.'

'Jaysus, what's happened?'

'I tell you what, Terry, it's Sunday morning and when I got the message, they said it wasn't urgent but when I went in, that excuse for An Garda Síochána was trying to get his bike started; kick starting wasn't the word; I looked down and he hadn't turned the bleedn' petrol on.'

'Who is it?'

'Diarmuid Brady.'

'Isn't that the one they called Blind Pew?'

'The very fella' said Mary. 'won't wear his glasses - if I stay much longer he'll be in the toss school.'

'Were they out there?'

'They all ran in when they heard us coming – that bleedin motor bike can be heard for miles.'

She took a warrant out of her pocket.

'Here look' - she showed Theresa the warrant 'and search for blood.'

'Unbelievable' said Theresa 'Are you sure it says blood.'

'Have a look for yourself.'

Theresa looked at the warrant 'it's blood - if that's a 'b' it's blood – could it be a flood?'

'It's blood' said Mary 'I think somebody's acting the shite.'

The place was clean and when she went out front, just as he said, the toss school had returned and Diarmuid Brady, Blind Pew, was tossing with them. 'Come on, Pew, we're away.'

'I'm down a few bob' he said 'can we hang on?

'Get on or I'll ride.'

'You will in your hole.' said Brady.

With that, he got on the bike and they were away.

The next day, Theresa went to see Carmel at The Coombe. She was out of bed, sitting in an armchair breast feeding Finbar. He was wearing a little link I.D. wrist band on with the words Esther Tuite.

'Did you see what the head nurse did – she changed his name to that of a girl – look: Esther Tuite.'

She pronounced it Chew it.

'No it's pronounced Tuite – it rhymes with boot, or cute. There was a one in Síle's class at school and they called her 'Tuite the boot.'

'Many kids still at home?'

'No they've gone' said Theresa 'Daragh was the last to go: not a boy any more; got one of his own now.'

'That's lovely' said Carmel.

'Lives out in Port Marnock in a caravan; no work. I'm on my own and I said they could come and move in with me – but they prefer to be by themselves out there – hoping to get something from the corporation.'

'Your husband still around?'

'No he flew the coop years ago – went t'England. Did they ask any question in here about your labour?'

'No, why would they?'

Theresa stroked Finbar's head.

'He's like an angel, isn't he?' she said.

'Why would they ask about my labour?'

'Nothing – I'm not a nurse any more and I thought they might be asking about me.'

Patrick and Joe joined them as it was the start of the visitors' period.

Patrick and Joe had a conversation as they walked home from seeing Carmel and Finbar. They chuckled at the idea of him being treated as a girl called Esther, and could only wonder what the shock might be if a nurse, who wasn't in on the act, changed his nappie.

'First things first, Da, we have to figure out how we're going to get Carmel and the child up to Carmel's friend's house?' said Patrick.

'Easy' said Joe 'you can take Finbar in the barrow and Carmel on your horse.'

'What?'

'Have you heard of such a thing a a taxi cab?' said Joe.

Patrick nodded his head.

'There we are then; problem solved.'

A week or so later Carmel was ready to be discharged and as they were walking out, Patrick carried the baby, and Joe had her things: she held on to Joe's arm to steady herself as they neared the exit.

'The taxi's out front' said Joe.

Suddenly Carmel stopped: just outside she saw her mother, in the distance, standing at the top of the steps outside with an old nun. Carmel pulled on Joe's arm and the two of them stopped.

'There's my mother.' she said.

'Pat!' said Joe.

Patrick stopped.

'Give Finbar to me and go around to the back entrance.'

'Why?'

'If you learn one thing in life son – never ask why – she saw her parents outside.'

'It's only my mother' said Carmel 'with a bleedin' nun.'

'Bleedin' from you?' said Patrick 'must be urgent.'

'She doesn't know me' said Joe 'so I'll take Finbar and get the taxi to meet yiz round the back.'

They did this and Patrick took Carmel another way. As he got closer to Mrs. Wilde and the nun, Joe wasn't really sure that he wouldn't be recognised, so he looked straight ahead as he got closer. Mrs. Wilde had her eyes fixed into and beyond the doors of the hospital, and as Joe walked passed the nun, she looked at Finbar and Joe, as he went through the outside portico, he noticed the nun's cross, around her neck: it didn't have the figure of Christ on it; a protestant.

He got in to the waiting taxi which was ticking over.

'All set?' said the driver.

'We have to go round the back.'

'Why?'

'Why!!! Bleedin' zed – to pick the others up.'

They set off; it didn't matter which way they went as Joe didn't even know there was a back.

'Smoke if you like.' said the driver.

'No thanks.'

'Do you have any?'

'What?'

'Smokes - cigarettes? I'm bursting for a pull.'

'G'long and bip' said Joe.

They arrived at the back and there they were: Carmel and Pat standing in the street.

'Ah, here they are.' said Joe.

The cab pulled up and they piled in after the driver put Carmel's stuff in the back. Pat sat in the front and the driver got back in, and as soon as he got in Patrick recognised him.

'Martin bleedin' Keogh – ex of Clerys no doubt?'

'Oh' said Keogh.

'What happened to Clerys?'

'We parted ways.'

'I wonder why – er Harbour Road, Dalkey.'

'Dalkey? Nobody said anything about Dalkey.' said Keogh.

'Any problem?' from Patrick.

'I might not have the gas.'

'What are you talking about, yeh galoot – don't ya fill up when you start work?'

'Well yes, but . . .'

'Pull in to the first petrol station and I'll get it and you can take it off my bill.'

'All right' said Keogh and drove on.

'It's not much of a drive, y'know – maybe twenty, twenty five minutes or so.' said Patrick.

'All right – do you know the way?'

'South?' said Patrick 'keep the Liffey behind us – and pull in to a petrol station to get some gas.'

The baby was asleep in the back and Joe was enjoying the ride when Keogh said 'Do you have your Sweet Afton?'

'What?'

'I'm bursting for a smoke.'

'You're not smoking in here' said Carmel 'there's a tiny pair of lungs in the back here and a fella who was gassed during the great war.'

'Here' said Patrick, and he handed him a cigarette which he put behind his ear.

'Smoke it when you get out' said Carmel.

Patrick looked at the petrol gauge and it looked very low.

'I think you can get some petrol at Drumcondra Bridge. Head on over there before we run out.'

'That's if they have any petrol left.' said Keogh.

'Do you have your coupons with ya?'

'What?' said Keogh 'coupons?'

'Oh no' said Patrick as they pulled into the filling station on, 'We may need coupons.'

Patrick got out and asked the fella at the place if he could spare some petrol.

'You'll owe me' said the fella.

'I can pay now.' said Patrick.

'I mean you'll owe me the petrol coupons.'

'Okay' said Patrick not knowing where he'd get them from.

'And I can only let you have a gallon.'

Keogh got out of the car and took his Sweet Afton and a match. He lit up just as the man was passing to get the petrol pump; he grabbed the cigarette just as Keogh lit up, threw it on the floor and put his foot on it.

'What kind of a gob shite are you?' he said 'trying to blow us all up.'

Patrick paid the man two shillings and a penny (2/1d) for the petrol and off they went. Keogh had no idea how to get to Dalkey even though most of the population of Dublin did.

When they got to Harbour Road, he asked for the number of the house, but Carmel shouted out 'that one' as she saw Aisling waiting by the wall.

It was a huge white house called Casa Blanca, roughly translated from the Spanish to house white or, as is accepted in translation, white house. Whoever gave it a name had a great imagination but it was a beautiful looking place.

Carmel and Joe went inside with Finbar, and Patrick waited with Keogh 'What are you going to do now?' said Patrick 'gonna take it back to where you got it?'

'I borrowed it. I went to see Paddy Byrne to see if he had any work and he told me to take the cab and see what I could pick up.'

'Did he ask you for any money?'

'No – in fact I don't think so.'

'You make sure he doesn't. Here.'

He handed Keogh a ten shilling note.

'What's this?'

'Your fare' said Patrick.

'What about the petrol money?'

'Forget that – there should be enough in the tank to get you home.'

'Thanks Pat' said Keogh 'your Da stopped me and I thought this must be my lucky day.'

'Till you looked at the petrol gauge?'

“Yeh.'

'You seem to be at a loose end – looking for a job?'

'Ah, I'm just a dreamer.'

'You know – if you applied to be a priest you wouldn't have to do any work apart from pray.'

'What do you mean?' said Keogh.

'Just a thought: what's the difference between dreaming and praying?'

'Dreams sometimes come true.'

'What about prayers?' said Patrick.

'The same – sometimes.'

'Don't forget those coupons.'

Patrick gave the packet of cigarettes and shook hands with him who got back into the cab and drove off.

Patrick went around the house to the back garden. He stood looking through the bright sunlight at the waves lapping onto the shore.

Two deck chairs were neatly placed looking out to sea.

The Irish Sea: which the Irish have to cross to see the world.

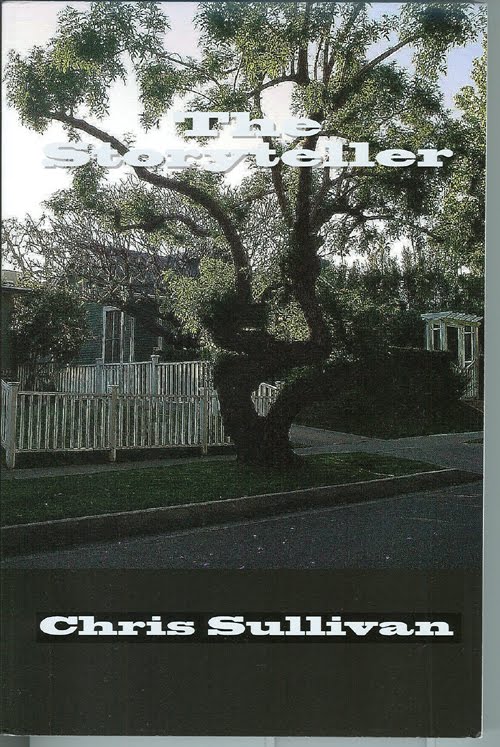

© 2025 Chris Sullivan

THE CALLAGHANS

PART 2

INTERMISSION

THE TRIP

Chapter 1