Portobello

Road; W10

by

Chris Sullivan ©2017

It

was nineteen-ninety – a new millennium, we called it, although the

millennium proper with all its problems and terror was ten years

away.

I

was standing on the corner of Portobello Road and Cambridge Gardens,

looking for my pal, my old buddie Barry. It was seven-thirty in the

morning and I should have met him at six. I knew he'd still be

around, somewhere, as we had come to search for bargains. We were

going to be high end antique dealers and millionaires. Barry had

been watching The

Antiques Road Show

on television, he had a Miller's

Collectibles book

and

I was a subscriber to The

Antiques Trade Gazette

and Exchange

& Mart;

so we were ready to go.

Portobello

Road was and is quite an atmospheric location to hang out on Friday

mornings, so I didn't mind too much as there was plenty to see: up

the street I could see the junk dealers and gypsies loading their

stalls; someone had brought their merchandise and rubbish on a horse

and cart and as the cart was being unloaded the horse stood there

depositing garden fertilizer on to the road surface, which used to be

called the horse road in years gone by.

One

solitary horse in a street; a street which was part of a city which,

a hundred years before, would have housed, or stabled, two hundred

and fifty thousand of them. Each week, hundreds or so dead horses

would be taken from London to be disposed of, together with many

millions of tons of horse manure for agriculture.

In

some parts of the world, and not too long ago in London, people would

run out from their dwellings and collect the dung with a spade and

fill buckets as the manure was great for their gardens. This time it

just lay there, steaming.

It

is supposed to be good for agriculture because horses don't fully

digest their food if it isn't grass; bits of undigested oats in their

excrement feed the sparrows too but these days there are very few

horses about and consequently very few sparrows.

Somewhere

in the melee of dealers and boxes was Barry and as I looked for him

at the junk end of the street I knew that behind me, under the

canopies and stalls with covers, was the posh end.

Jim

had told me that on the posh side many many thousands of pounds would

change hands before dawn every Friday; Friday was the trade

day

and Saturday was for the tourists and public.

Jim

was a gypsy from Ireland; he cleaned out jumble sales and car boot

sales and brought everything to Portobello Market, and whatever was

left at the end of the day he would donate to the local tip where

other dealers would buy the stuff from the people in charge.

He

seemed to do okay spending most of his holidays touring the continent

in his tiny caravan with his wife and large family. As I looked

around for Barry I could see Jim standing on the other side of the

street, behind his stall, smoking a cigarette and sitting on a pile

of cardboard boxes.

'Hi

Jim' I said as I walked to his stall.

'Did

you do any good?'

'I've

just arrived' I said 'have you seen Barry?'

'I

told you to get here for six if you want to stand a chance' he said

sarcastically, puffing on his fag.

'I

overslept' I said.

It

seemed a bit of a strange thing to say, at that time of the morning,

- I had been up since dawn! How can that be oversleeping?

I

had dashed out of the house, driven like a maniac down the A40,

luckily found a parking spot in Ladbroke Grove and walked along

Cambridge Gardens to the spot I said where I would meet Barry all

before seven thirty; very unusual for me!

'Have

you seen him?' I asked again.

'I

just arrived myself' he said, as he took out another fag and lit it

on his old one: 'I'll unpack as soon as I've had my smoke.'

'Think

it'll be a good day, today?' I said.

'These

days people don't want to spend any money.' he said.

I

left him complaining and moaning and going on about back

in the day

and how things used to be when you could buy a twopenny cigarette and

a cup of tea for less than a quid.

We

came here at Jim's suggestion – we?

- where was Barry? But it doesn't matter where you go nothing is the

same – and why would it be?

In

my day people had rickets!!

The

pair of us, me and Barry, and even Barry and me, were novice antique

dealers. He knew a lot more than I did and I was learning as we went

along. I had a few bob in my pocket, from being made redundant, and I

wanted to make money with it as opposed to pissing it up the wall or

losing it at the bookies; if we saw something cheap, that we could

sell at a profit, we'd buy it.

We

went to antique fairs, car boot sales and auctions: learning all the

time, buying a bit here and a bit there. Antique Fairs were funny;

little old ladies hiding behind a great pile of porcelain doing their

knitting; they didn't seem to be in business at all. It was as if

they'd taken the contents from their front room to display at the

local church hall or hotel. If anybody asked how much something was,

the stall holder would come out from her knitting, stand in front of

the table, and give a full history of whatever was for sale.

All

the customer wanted to know was the price!

I

think the only good thing about those kind of fairs with the

ridiculously high prices was that some of the prices are sometimes

ridiculously low!

Barry

bought a piece of Clarice

Cliff

one day from a 'know all' dealer for ten pounds and sold it to

another for a hundred.

There

was a little bit of an alley way near Jim's stall which led to

another road where there is sometimes a parking space where Barry

would park if it was available. All I had to do was to look for the

blue Volvo with a load of smoke coming from it and I would inevitably

find Barry. It didn't take long; there was no smoke, as he wasn't

smoking, but I saw the silly roof rack first.

Barry

had gone in to debt for the car and it looked quite smart – apart

from the roof rack which was about twenty years older than the car

and made it look quite scruffy – a nice blue Volvo and a scruffy

roof rack!

He

was sitting in the front seat, reading a newspaper and scoffing a bag

of chips. That was the nice thing about the neighbourhood

on market days; you could buy chips from dawn.

I

knocked on the window and he pressed the button and it opened 'where

you been?' he asked.

'Overslept!'

'Silly

bugger.'

I

thought he was going to continue reading his newspaper when I saw him

turn away but he was reaching for something under the seat.

'What's

that?' he said, holding up a candlestick.

'A

candlestick?'

'I

reckon that's Sheffield

Plate'

he said, stuffing it back under the seat.

I

knew that Sheffield Plate was a fusion of copper and silver plate –

something like that – as I'd looked it up in Barry's book but I'd

never seen it before.

He

told me that he'd spent all his money and hoped for about three

hundred profit – if he could sell it all.

He

got out and we walked off 'I'm going for a cuppa – do you want

one?' he said.

I

nodded and told him I was going to give it a try no matter how late I

was and left him.

As

I walked back to Portobello I saw an attractive young red headed girl

talking to Jim as he was putting his goods out on the stall.

As

I approached, Jim said 'watch this fella - he'll bite your hand off

for a bargain.'

'Take

no notice of Jumble Jim, love' I said 'when he's not here he's at his

villa in Spain.'

'I

wouldn't mine being in a villa anywhere today' she said as she rubbed

her hands together.

Jim

took some kind of scroll out from one of his boxes; I picked it up

and opened it slightly and I could see Hebrew writing – The Dead

Sea Scrolls? I thought.

'How

much?' I asked.

'Fifty'

said Jim.

I

put it down.

'How

much did you say?' said the girl.

'Fifty'

said Jim 'fifty pence.'

'You're

on' said the girl giving him a fifty pence coin and walking off with

the scroll.

I

stood there with my mouth open. Fifty bloody pence and I thought he

meant fifty pounds.

'See

you Jim' I said and walked after her.

She

went behind one of the stalls at the posh end then Barry stopped me

and bunged a cup of tea in to my hand.

'Who's

that girl?' I said

'What

girl?'

'That

red head there. Going behind the stall' I said between gritted teeth.

'Don't

know – must be casual' he said, adding 'why do you fancy her?'

'She's

just bought a Jewish scroll from Jim. Go and find out how much it is'

I said as I took Barry's tea from him before walking over the street

and ducking behind a car.

I

watched Barry talking to her; I didn't really want her to know I was

still interested. They chatted and he came back.

'How

much?'

'Hundred

and fifty pounds' he said.

'How

much?' I repeated.

'One

hundred and fifty pounds.'

'You're

joking.'

'I'm

not' he said 'it's cheap; must be worth about six hundred.'

'Are

you sure?'

'Maybe

more' he said 'and I'm skint.'

'If

you're sure we'll buy it between us – fifty fifty.'

I

gave my cup of tea to Barry and walked towards . . . towards the

scroll.

'Hello

again' I said to her 'guess what I'm after?'

She

lit up a cigarette and shrugged.

'I'll

give you a profit on the scroll.'

'Sounds

fair' she said and she kind of batted her eye lids at me as she took

a huge pull from her fag.

'How

does a fiver sound?' I said.

'Sounds

terrible' was her reply - 'I told your pal the price when you were

hiding behind that car.'

'You

saw me?'

'I

saw you.'

I

took three fifty pound notes from my back pocket.

'Is

that your best?' I said as I picked up the scroll and handed over the

money.

'You

want me to knock something off?'

I

nodded.

'How

does a fiver sound?' she said.

'Terrible.'

I said and I took the fiver.

Just

along Cambridge Gardens is a tiny park; Portobello Green. It seemed

to attract drunks and the down and outs from the neighbourhood; I

thought the best thing to do was to go in there, sit on a bench and

look at it.

'Where

you going?' said Barry as I swept past him.

'To

look at it.'

'What

about your tea?' he said as he trotted up to me.

'Come

on' I said and we went into the park.

The

place was full of drunks, as usual, with the signs of drug taking and

condoms by the only vacant bench. Barry came running up behind me

intent on making me drink the dreaded tea.

'Don't

run, Nick' he said 'they'll think we pinched it.'

I

wasn't running just walking fast; I couldn't wait to have a look. I

approached a man who had either fallen or taken a severe beating. The

right hand side of his face was covered in cuts and his forehead had

a large newly formed abrasion; he muttered something as he staggered

past.

'You

okay, mate?' I said.

'Do

you have fifty pee?'

I

gave him a pound coin and sat on the bench. Barry sat beside me and

put the tea into my hand as I handed the scroll to him.

He

looked at the outside, turned it around to see if it was straight or

not then, very carefully, unrolled it and looked at the Hebrew

writing. His face was filled with wonder and appreciation.

'It's

worth a lot more than I thought' he said, looking at me; I could see

a tear in the corner of his eyes, 'it's worth millions and millions;

as much as you can imagine.'

'That

much?' I said.

'That's

what it's worth' he said 'but you want the price.'

I

nodded.

'Bring

this to me at Covent Garden on Monday and I reckon Invernezzi will

give me a couple of grand for it; maybe more.'

'Take

it with you.' I said.

'No

no – it's yours – I haven't parted with any money yet.'

'I

said fifty-fifty; I wouldn't have known how much it was worth; I

never saw one before.'

He

looked at me with that look he always gave when I've said something

silly 'I've told you before' he said 'anything Jewish is always worth

buying.'

He

handed the scroll back to me very carefully, as if it was thousands

of years old; it might have been, for all I knew.

A

man came into the park; he was walking very slowly and it was obvious

that he was coming towards us. He wore a white trench coat and a

black trilby hat and as he walked he was rubbing his jaw as if it

helped him ruminate. His body movement together with his appearance

reminded me of a Jewish Humphrey Bogart. I looked at him and a half

smile lit up his face.

'Who's

this?' I whispered to Barry.

'Good

morning' the man said in a crisp and clear New York Brooklyn accent

'I'm interested in what you got there.'

We

looked at him.

'Do

you mind if I take a look?'

'Take

a look?' said Barry.

I

looked at the man; was the scroll hot? Was he the police?

'I

saw you purchase it at the market there – I missed it by a

whisker.'

'Sit

down' I said.

He

did; between us. I gave him the scroll. He took it and, looked at it

very closely. 'No cover?' he said, looking at me.

I

looked at Barry 'cover?' I shrugged.

Barry

looked at the man 'no' he said.

'Naked

as a baby' said the man, almost to himself.

He

seemed to know a lot about it and understood the Hebrew, smiling

slightly as he read it.

'Is

this for sale?' he said.

'It

will be' I said.

Barry

didn't look too pleased.

The

man continued to look at it then looked at Barry and said 'how much?'

Barry

looked at me 'Nick?'

'A

thousand' I said.

Without

missing a beat the man said 'dollars or pounds?'

I

gulped 'pounds!'

He

smiled to himself 'I guessed as much.'

He

looked back at the scroll; Barry looked at me and I winked; I knew

this fella was interested.

'How

does a thousand dollars sound?' he said.

'How

much is that in pounds?' said Barry.

'About

six hundred' said the man.

Sounded

fair enough to me; I put my hand out to shake on the deal but he put

the scroll into it 'what about a thousand dollars and fifty pounds

cash?'

He

really wants it, I thought, as I nursed the scroll in my lap. In the

distance I could see the man, to whom I had given the pound coin,

settling down for a rest behind one of the benches.

I'll

hold out for more money, I thought; I turned to look at Barry whose

face was a picture; I remembered he said he would get a couple of

grand from Invernezzi at Covent Garden.

'Sorry

I can't do it' I said, I was really playing the big dealer now; Barry

looked a bit shocked, 'I'll get two grand at the garden.'

'The

garden?' he said suddenly, obviously thinking of Madison

Square Garden

in New York.

'Covent

Garden' said Barry.

'On

Monday' I said.

He

took his hat off, revealing his bald head, and started fanning

himself with it; then he put it back on.

'Gentlemen'

he said 'I really didn't come out to spend that kind of money.'

He

looked at us; we didn't respond but the three of us looked ahead. The

man who had settled down for a sleep was getting up and started

walking towards the park gate.

'My

name is Green' our man said 'Martin Green; if I can meet you tomorrow

I'll give you . . .' he paused for a moment; as he did he looked at

us, his bright brown eyes darting from one of us to the other; he

took a deep breath 'two thousand dollars and three hundred English

pounds.'

'That's

about nine hundred pounds' said Barry.

'No

it's not' I said 'It's . . .about . .'

'Fifteen

hundred' said Martin Green 'Pounds.'

'It'll

still give you some profit' I said.

He

looked straight into my eyes. 'This is not for profit; this belongs

in the place of prayer.'

Barry

laughed: 'we thought you were a dealer.'

'Gentlemen'

said Martin Green 'I'm flying home tomorrow night and I'd like to

take this with me; can we do a deal?'

I

said 'If you'll excuse us for a moment I'll let you know.'

'Excuse

me' he said.

'We

need to discuss it.'

'Oh

oh' he said, and jumped up from the bench.

'Sure

sure' he said and walked off around the park.

When

he was out of ear shot I said to Barry 'what do you think?'

As

usual he threw the ball back into my court 'It's not up to me it's

yours.'

'Fifty-fifty'

I said.

'In

that case it sounds okay. I would have been happy with his first

offer.'

Martin

Green was still walking and the way he was heading would bring him

back around to us; so I waited for him to get closer.

'Okay'

I said 'it's a deal.'

It

seemed to release a big weight from his mind and his face lit up into

a big smile.

'Great'

he said 'I'll meet you here tomorrow – same time?'

I

looked at my watch; eight-o-clock.

'Do

you have a card?' he said 'in case I need to reach you?'

A

card? I didn't even have a piece of paper. I threw the remnants of my

tea away and tore a small piece of polystyrene from the cup and wrote

my number on it.

'Here'

I said 'that's my home number but I won't be there till later this

afternoon.'

'But

we'll be in the Latimer Arms between eleven and twelve' chipped in

Barry.

Martin

Green wrote Latimer

Arms

on the piece of polystyrene I'd given him. He smiled and put it into

his pocket. I gave him my hand to shake 'Nick Murphy' I said 'good

doing business with you.'

'Likewise'

he said and walked off out through the park and into Cambridge

Gardens. We watched him walk away.

If

this was Portobello Road we would certainly come again.

It

was four-o-clock in the morning in New York City and Frank was fast

asleep in his apartment. The phone rang, next to his bed and he woke

up with a jolt. He could see his clock illuminating the time at him;

four-o-clock in the morning was not a good time for Frank. It was

four-o-clock in the morning three years earlier when he got the call

to go to the hospital. His beloved wife Rachel had died but the

hospital didn't tell him that. They spared him the shock and just

told him to come in as she had taken a turn for the worse. When he

got there they told him. Frank picked up the phone; it was Martin –

Martin Green.

'Hi

Frank' he said 'did I wake you?'

'No

Marty' said Frank 'I just got out of the shower.'

He

swung his legs to the side of the bed; it felt good doing that as he

could do little else so sprightly at his time of life; he reached for

his spectacles to await the bad news then he realised:

Martin was in London.

'Good'

said Martin 'I'm badly in need of some rabbinical advice.'

There

was a glass of water, Frank always kept, on what he called the

nightstand, which he reached for to let Martin give him the news

about Portobello Market. He let the water freshen his mouth as he

listened, intently.

'You

want us to give it a home, right?' he said to Martin.

'Right'

said Martin.

'You

betcha.'

Frank

would give various talks about amusing aspects and histories of

Jewish Law, and one time spoke about a huge stockpile of scrolls

found in Czechoslovakia after the war. The Nazis final

solution

to exterminate the Jews also included the establishment of a Jewish

museum to celebrate

the extinction

of the Jews;

the scrolls were going to be a part of that. It was said that they

were sent to Britain, and were then sent to various synagogues,

throughout the British Isles, who were charged the princely sum of

£100 each. Martin had remembered that Frank referred to the museum

as a weird

Nazi Museum.

'I'm

glad you have it' said Frank 'I wouldn't like to see a Sefer-Torah

going

to some screwball collector to hang on his wall.'

'Well'

said Martin 'I offered the guy my last two thousand bucks, which I

will give him tomorrow when we . .'

Frank

interrupted 'You mean you don't have it yet?'

'No

I gotta meet him tomorrow – he might even try for more money . .'

'I'd

be surprised if he doesn't.'

'Why?

How much is it worth?'

'Work

it out for yourself' said Frank 'hand written on parchment, a year of

someone's life: and how old

it is.'

Martin

gulped audibly down the phone.

'If

we were to go out today, Marty, to buy a Sefer-Torah

we would have to pay at least ten thousand dollars.'

'Ten.

. .' Martin stammered 'you're kidding.'

'Get

on to the guy right away, Marty, right away, before someone else

comes in with a better offer. Pay him the full price and I'll wire

you the difference.'

I

looked at the scroll, which I had cradled in my arm, as Barry was at

the bar getting my Guinness. What cover did Mister Green mean? I

supposed it would be some kind of velvet thing; Barry had said he saw

a picture of a scroll when he attended night school for antiques. I

hadn't bothered to go but Barry said he enjoyed it and got a lot out

of it. He came back with the drinks.

'Not

a bad day's work today' he said.

'Here's

to plenty more' I said, clinking the glasses.

'I

thought you blew it back there for a minute' he said.

'When?'

'When

you said you couldn't do it.

'I

knew he wanted it' I said 'cover or no cover.'

The

barman shouted over 'Is there a Nick Murphy here?'

'Yes'

I said.

'Phone

call' the barman said and put the phone on the counter.

There

was only one person who knew where I was and that was Martin Green.

'Mister

Murphy – Nick' came the unmistakable Brooklyn accent down the line.

'Yes.'

'Martin

Green; remember me?'

'Of

course I do.'

'I

really want that . . that item I saw today.'

'I

know you do' I said, looking at the scroll in my hand.

'I've

just been on to New York and I am authorized to offer you eight

thousand dollars.'

Eight

thousand dollars! What was the matter with the man? We had already

made a deal. What could I say?

'How

much is that in pounds?'

'About

five grand, I guess' he said.

'Sounds

great' I said and it did. I couldn't believe it.

'Do

we have a deal?' he said.

'We

do.'

We

did indeed.

'It's

gonna take me a little time to get the cash together with transfers

and so forth and I'd like to meet tonight?'

A

thought, a profound thought had entered my head, so I told him we

should keep to the time in the morning as I was busy that night.

Barry

was standing next to me; he couldn't hear any of the conversation but

he knew it was good news and I could see by his eyes he was excited.

'Don't

tell me' he said 'he doesn't want it?'

Barry

is as dry as they come but he looked at me eagerly for the price.

'You'll

never guess how much he's offered' I said.

He

looked at me in anticipation.

'Five

grand' I said 'straight in, no haggling, five thousand pounds.'

Without

a smile, a twinkle in the eye or anything else Barry said 'it must be

worth more than I thought.'

Damn

right it was; that was the thought I had when I was talking to Mister

Green on the phone; how much more?

'Call

Invernezzi now' I said 'see how much he'll pay.'

'What

about Mister Green?' he said.

'If

Invernezzi pays more forget Mister Green.'

'Play

one off against the other' said Barry. I nodded 'I like it' he said,

with the same straight face.

The

telephone was still on the bar and I could see Barry asking

permission, then taking out his address book and dialling.

I sat back and took a sip from my pint as he returned.

'No

answer – he must be out buying' he said.

'Okay'

I said 'call him when you get home and tell me about it tonight.'

'Tonight?

What's happening tonight?'

'We'll

take the girls out to celebrate' I said 'I'll pay.'

'I

like it even more' he said as we clinked the glasses together again.

Getting

up at dawn and ending with a quick pint in the pub always affected me

the same way; I wanted a nap. So that was what I planned the minute I

walked through our front door.

I

opened the door and there was silence; nobody in. I was glad in a way

as it meant I could go straight to bed without having a chat with

Helen. I dropped the scroll onto a suit-case in the hall and called

upstairs in case she was in; no reply. On the table, in the kitchen,

was Helen's cassette recorder with a card on top which read

Play me!

I pressed 'play' and sat back in anticipation:

'Hello

my darling' she said 'I've gone to Judy's for the afternoon and I'll

be back at about five; byeee.'

Then

she made herself laugh and switched off.

I

had to have a go as well so I turned the card over, wrote play

it

again Sam

on it, recorded my message and went to bed.

I

slept like a log and didn't hear Helen come in; she saw my note and

played my message telling her that I had had a great day and to wake

me at about seven as we were meeting Barry and Sue for dinner.

Whilst

she was listening to my message there was a ring on the door bell;

she broke off to see who it was and standing on the doorstep was a

little boy 'jumble?' he said.

'This

lot here' said Helen and went back to the recorder.

The

little boy, a boy scout, picked up the suitcase, with the scroll on

the top of it, and went out; 'bye' he shouted and that was that.

When

I came down the stairs the first thing I noticed was the vacant space

by the last step where the suitcase had been – together with the

scroll.

'Helen'

I called.

She

came out of the sitting room 'where's the case that was here – with

a scroll on top of it?'

'The

boy scouts have it for their jumble sale; just some old . . .'

I

ran to the front door, wearing only my towel robe 'where is he?'

'He

was here a couple of hours ago – the sale is tonight.'

'Come

on let's go' I said, and I picked up the car keys from the hook and

ran to the car.

I

didn't know where the sale was supposed to be and neither did Helen.

There were a few places we could try, which we did, but by the time

we got to the last sale it was around eight-o-clock and that one had

finished.

Helen

looked at me 'sorry' she said but it wasn't her fault and I told her.

She wept a bit when I told I had spent a hundred and forty five

pounds and when I told her the full story she was really sorry but

instead of bursting into tears she started laughing. I was wearing

nothing but a towel robe and we both had a laughing fit for some

time; it was my fault for being greedy.

The

worst part of the whole affair is that there was a man called Martin

Green who really wanted the scroll and now he wasn't going to get it.

The

next day I met Barry at Portobello Road as planned; he hadn't 'laid

out' any money but he called me a few choice words. We went along

Cambridge Gardens to where we could see in to the park and the spot

where I was to meet Martin Green. He was there, already, sitting on

the same bench, wearing the same black trilby and the Humphrey

Bogart

trench coat. He sat there; occasionally looking about with a look of

half knowing that I wasn't going to show, one minute, and a look of

anticipation the next.

It

took me a long time to make up my mind that I wouldn't make an

appearance. It might sound like cowardice, and maybe it was, but as

soon as he would see me coming his expectations would lift and he

would expect me to have the goods.

Barry

went off to the greasy spoon café

just around the corner to order our breakfasts and I said I would

meet him in there.

After

a few minutes, and maybe twenty minutes after I had arranged to meet

him, Martin Green got up from the bench and started to walk towards

the gate; he would be mulling over what to say to his pal in New

York. Frank would probably meet him at the airport and tell him he

had found a place on the wall just outside the portal of the shul

to show a sefer-torah which had been stolen by the Nazis and rescued

by Martin.

I

walked along Cambridge Gardens as I didn't want him to see me and hid

amongst the second hand clothes on one of the stalls. He stopped on

the corner of Portobello Road, the place where I had waited for Barry

twenty four hours earlier; was it really only twenty four hours?

He

stood there for a few minutes, not too far from the greasy spoon café

where

Barry was; I prayed that he wouldn't come out. But Martin was looking

for me. Opposite Martin I could see Jim – Jumble Jim, setting out

his stall and puffing away at a cigarette. He wasn't greedy – not

like me – he would buy stuff for very little and sell it for a bit

more and that's how he managed to travel each year.

Martin

took off his hat and fanned it in front of his face and I moved along

the second hand clothes rack to where I could see both Martin with

Jim in the background.

Martin

put his hat back on and wandered over the street to Jim. They chatted

for a while and as they talked I could see Jim take the scroll out of

a cardboard box the way he had done the day before– at least I was

sure it was the scroll. Martin looked at it; he didn't move; didn't

say a word. Again he took his hat off; he didn't fan himself but

stood there motionless with the hat in his right hand.

'How

much?' he said.

'Fifty'

said Jim.

Martin

picked up the scroll and cradled it gently in his arms as I had -

like a baby. He had five thousand pounds in his pocket for me and no

loose change. Should he give this man five thousand pounds? Would

that be the moral thing to do? He looked at Jim: a gypsy, he thought,

the Nazis took these scrolls from us, exterminated both my people and

his and now God is getting it back to me through a gypsy.

That's

what Martin was thinking as he reached into the top pocket of his

jacket, underneath the trench coat, where he kept some fifty pound

notes. He took one out and handed it to Jim.

'Fifty'

he said.

Jim

said 'I have no change. . .'

But

Martin held his hand up to quieten Jim who put the fifty pound note

into his pocket.

'Thank

you, sir' he said 'thanks very much.'

I

wasn't

sure at this stage what Martin had bought; it looked like the scroll

but I still wasn't sure, then I realised

that Jim cleared Jumble sales; Jumble

Jim.

Of course. Nobody had bought it, it had remained on the counter for

the whole sale and when they were clearing up Jim came, made them a

job

offer

and took everything off their hands.

Martin

Green turned around, crossed back over Portobello Road and walked

towards me. It was too late for me to hide so I carried on walking.

Martin wasn't looking at me, he was in a world of his own; everything

had fallen into place after his day of trying to get the money wired

over from New York and then finding a bank where he could transfer it

into cash, and I was happy for him; I really was. To hell with the

money.

As

he got closer he caught my eye and as he passed he lifted his hat. I

could see the end of the scroll under his trench coat and when we

crossed he winked at me; 'I got it' he said and he was gone.

THE

END.

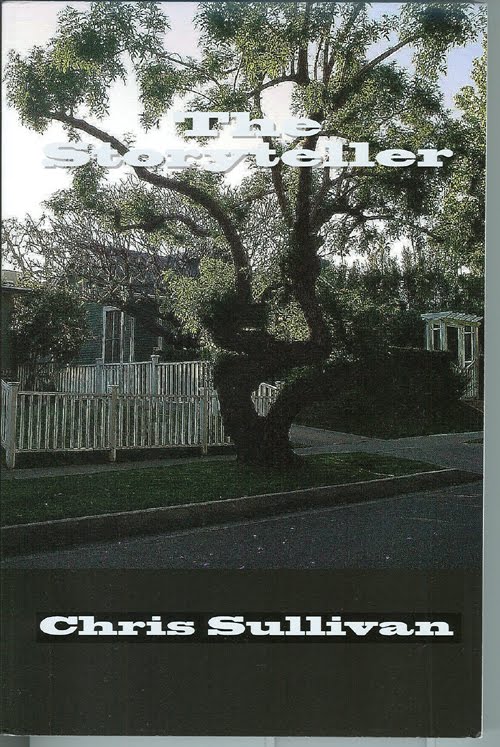

I wrote a screenplay for my film The Scroll around 1989 or so and not long before I went to America in 1994 I adapted this short story from the script. I found it the other day and wrote this draft; let me know what you think.