At six forty five, every weekday evening, Sydney tuned the radio, or the wireless, as he called it, to The Home Service. First of all he had made sure the battery had been charged at Barrett's Record and Music Shop so he could listen to 'The Archers;' the daily serial.

The radio volume was set quite high and everybody in the four cottages could hear it blasting. They knew Dan Archer and Peggy, even though they had no interest in the programme at all.

Irene was sitting in her chair and Sydney almost had his head next to the set.

Upstairs in their spare room, which was but a box room, as Finbar's was next door, was a well made up bed for the boy to sleep on Saturday. There was plenty of time to shop for his Shredded Wheat and Weetabix, but even though it was only Tuesday evening, his breakfast was ready for Sunday morning in their small pantry. They knew he liked his breakfast with hot water, to soften the cereal, and covered in sterilised milk and sugar.

Irene and Sydney ate bacon and eggs for breakfast every day, which they had been doing ever since rationing stopped when they couldn't buy enough for breakfast. They had a friend in Balsall Heath Road and another friend in Ombersley Road, whom they would swap food with and between them they shared their rationing. Doll Cadell in Balsall Heath Road, didn't like eggs at all, so she swapped with Irene and Sydney in exchange for cheese.

Rationing per person in the UK, for one week, was one egg, two ounces each of tea and butter, an ounce of cheese, eight ounces of sugar, four ounces of bacon and four ounces of margarine.

Sydney hated margarine so that went to Doll Cadell.

Their friend in Ombersley Road, Mona Hunter and her husband Ron, were Jewish, and didn't eat bacon so Irene and Sydney had their bacon and Mona and Ron had Irene and Sydney's margarine. Lots of things like that but when rationing stopped Irene and Sydney had a fried breakfast every day and used plenty of butter – best butter they called it.

They had lived alone for eight years since their only son, Ralph, had moved to Berlin upon his marriage to Margo, a German girl, he had met when he was in Germany during the war. He brought her home to meet mom and dad but, as they didn't have room at the cottage, they stayed with Mona and Ron Hunter in Ombersley Road, but a German living in a Jewish household didn't quite click. She didn't seem antisemitic and they didn't seem anti German. So the couple went to Berlin and, even though they wrote for a couple of years, they lost touch. All they had was a Christmas card each year: To Mom and dad, with lots of love: Margo and Ralph. Hope to be over this year. And that was on every Christmas card which they kept in a drawer. They didn't talk about Ralph much but they were heartbroken and they looked forward to Finbar staying in Ralph's bed.

But when Saturday night came there was no Finbar.

Irene and Sydney didn't know what to do as they didn't miss him till about nine-o-clock. They were never sure of the expected time of his arrival and both of them waited up till midnight. They could have gone to the police station in Edward Road, which was a short walk along the main road, but they wouldn't have known what to say.

They were not expecting Carmel and Patrick till about midday or so, as they were due in Birmingham on the boat train from Holyhead.

At the top of the lane mister Murdoch was taking his car out and about to turn into Moseley Road when he was stopped by the horse and cart of a rag and bone man.

“Do you know South View Terrace, mister?'

'Yes, it's down the lane there – who do you want?'

'I

don't know' he said 'I found this bag.'

'oh?'

'It's for fun boy, or something like that.'

'FUN boy?' said Murdoch.

'Something like that. I found it in my travels and there's Birmanum twelve on it – on the label.'

'Let me see' said Murdoch getting out of his car.

The rag and bone man showed Murdoch Finbar's bag.

'I don't read too well and I found it on the road.'

'When was this?'

'Well I didn't find it. It was passed on to me by a colleague who wanders over there.'

'Where?'

'By

the Lickies'

'When was this?'

'Few days ago . . Wednesday, I think – I can see the figure twelve and I know what Birmanum looks like.'

'I see.'

'Somebody said it was around here – South View Terrace, I mean. I was told it was on the ground it was – the bag that is - at the side of the horse road. My colleage knew I come this way - as far as Varna Road, and thereabouts but there's no pickings here – load of hoi polloi round here?'

'hoi polloi?' said Murdoch.

' ''septing for your self, like – I mean I don't mean you, squire.'

Murdoch went to his car and turned off the engine.

'The

Lickey Hills?'

'That's what I said, well that's what he said.'

'Who?'

'The fella what found the bag.'

Murdoch was puzzled.

'What would you say if I said I know who this belongs to?'

'What

would I say? - I don't know.'

'Let me make it worth your while'

said Murdoch, putting his hand in to his pocket.

'Where at the Lickies?'

'Not far from the bottom of the hill – Rose Hill. I'll be honest with you guvnor, if it were worth anything I'd a kep' it.'

'Here we are' he gave him half a crown.

'Very

kind of you, sir – very kind.'

'Okay.'

'I'll be on my way – Finbar, you say?'

'Yes.' said Murdoch.

'I could see the love the kid – Finbar – had for his stuff. He had string in there with knots I didn't know about, and loads of words of poems or songs that I didn't understand and things - and I could see it was a little lad – you can let him have it?'

'I will, sir – thank you very much. I'll tell him a kind man found his bag.'

'Here look at the stuff' he said, opening the bag 'string, look! Loads of it – papers, look! Pictures of plants and mushrooms and such – look! A cowboy.'

He showed Murdoch the picture of Gary Cooper in High Noon.

He fastened the bag and handed it to Murdoch.

'We'll

be off.' he said 'I think the boy would be a kid after my own heart –

bits of twigs he had, a ball of string – but no money.'

'You

sure?'

'Cross my heart, guvnor, cross my heart.'

'Here' said Murdoch, and gave him another half-crown.

'Good man sir' said the rag and bone man as he grabbed the reins 'Good man - hucha.'

He and horse, headed south along Moseley Road pulling the cart and the rag and bone man to his next destination.

'Raga bowa – raga bowa' his voice faded into the distance which Murdoch could hear as he went down to Finbar's cottage leaving the car where it was. Sydney was standing at his garden gate.

'Hello, mister Melia - someone found Finbar's bag' he said as he passed Sydney 'Are they back from mass yet?'

'No – that's the trouble' said Sydney 'we don't know where he is.'

'Who?'

'Finbar – he's been away with the scouts - don't know where he is.'

Irene joined them.

'His mom and dad are on their holidays' she said 'and he was supposed to be coming to us last night, but he didn't come.'

'He was away with the boy scouts?' said Murdoch.

'Yes sir – his mom and dad are due back today.' said Irene.

'So Finbar's been missing since yesterday?'

'Yes sir' said Sydney.

'What time are Carmel and Paddy due back?'

'This afternoon.' said Irene.

'Leave it with me' said Murdoch 'I'll sort York out.'

'York?' said Irene.

'Scoutmaster.'

He went back up the lane, passed his car and went to Mr. York's house. His mother answered the door.

'Hello Mrs. York – is Alfred in.'

'Yes he is' she said 'Alfred?' she called.

Mr. York came down the stairs.

'Hello' he said 'What can I do for you?'

Mr. Murdoch drove his sports car to New Street Station, and waited as Mr. York went to find the time of the next train arriving from Holyhead. The station was at the bottom of a steep hill and as he waited there, Murdoch could see the platforms to his right and another to his left. In front of him was the other side of the steep hill; this time going up.

York had explained to Murdoch about calling the trip off and Finbar going off with a senior scout from Saint Agatha's troop.

'And you didn't check that he'd reached home?'

'To be honest, Doug, it went completely out of my mind.'

'Not good enough' said Murdoch 'we really ought to be calling the police – I mean who is this senior scout?'

'He was from the Saint Agatha troop – lives in Sherbourne Road.'

'Do you know him?'

'Slightly – Finbar didn't want to go with him. it sounded like some kind of fear of convertibles.'

'He was okay in my motor except for the rain.'

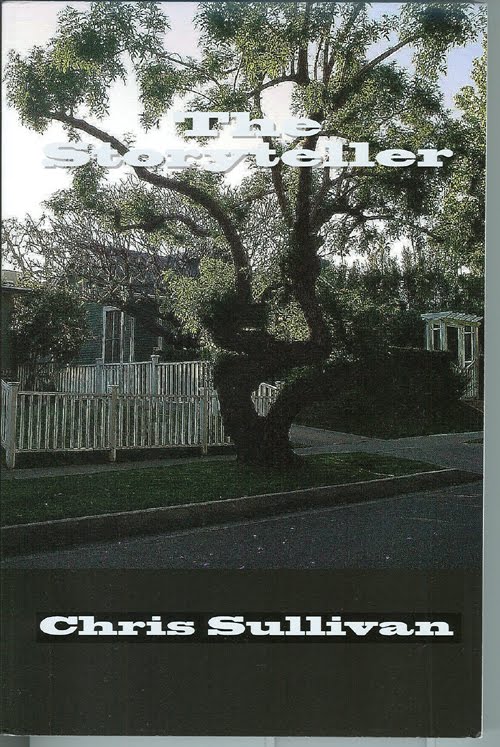

The fact that Finbar's bag was found at the Lickey Hills gave Mr. Murdoch – Mr. Douglas Murdoch; JP, by the way – ideas. He had noticed Finbar's fascination with the big tree, he seemed to see, which Murdoch couldn't, some kind of picture or etching on the inside, and was very comfortable leaning against what Finbar called a divine place to sit.

York returned.

'It's on time, Doug – be another five minutes they said.'

'How are we going to handle this?'

'How do you mean?'

'How do I mean?' said Murdoch 'What are we going to say to Paddy and Carmel about Finbar?'

Murdoch took out a packet of Senior Service cigarettes, and offered one to York.

'Senior Service' he said 'Must be doing well?'

'I've always smoked them – even when I was on my uppers.'

'Were you in the service?'

'Yes: Royal Navy – I was a Lieutenant.'

Eventually, Carmel and Patrick emerged from the station.

'Paddy' shouted Murdoch.

'Hello' said Patrick 'is this a royal welcome.'

'Afraid not;' said Murdoch 'I don't want to distress you but we're having a bit of difficulty locating young Finbar.'

'What do you mean?' said Carmel.

'If you get in, I'll try to explain.'

The Callaghans did no such thing 'What do you mean?' said Patrick.

'Where is he?' said Carmel.

“We're not sure.' said York.

'You're not sure?' said Patrick.

'We're not sure – we've just found his bag.' said Murdoch.

'We had to call the trip off on Tuesday, and . . ' said York.

Murdoch exited from the car and went around the back.

'You haven't seen him since . . you better tell me what's going on, fella – he went off with you and your scouts, and you've lost him.' said Patrick.

'Calm down, Paddy' said Murdoch.

'Don't be telling me to calm down! He's been missing for five days – where is he?'

'We had to call the . ' said York.

'Where is he?'

'We, we . ' stuttered York.

'Tell me now where he is.'

'I think I know where he is' said Murdoch 'the Lickey Hills.'

'The Lickey Hills!!!! And what's he doing there?'

'His bag was found there, and . '

'Have you been to the police?'

'No, Paddy – we've only just found out.' said Murdoch

'What?' said Carmel.

'If you'd both let me tell you . .'

'All right. I'm all ears.' said Patrick.

'What?'

'Go ahead – go on.'

Murdoch went around his car to Patrick 'the camp site was flooded so they had to call the trip off on Tuesday . . '

'And where's he been since then?' said Carmel.

'We had to organise a way . .' said York.

'You're making no sense' said Carmel ' if he's been missing since Tuesday, somebody should have gone to the police.'

'I'm trying to tell you' said York 'we had to take the boys from our troop and the Saint Agatha troop back in private cars. Dennis Reynolds took the Saint Agatha troop, young Daniel went back on the train and me and Tommy took our troops between us and as Tommy lives in Sherbourne Road - he took Finbar.'

'Tommy?'

'Yes' said York 'a senior scout at Saint Agatha's.'

'Let's get round to this Tommy, in Sherbourne Road?'

'We've been' said Murdoch 'there's no one in.'

Patrick recognized the name.

'Tommy? – the one who liked little boys?'

'What do you mean' said York.

'He hung around young kids – Finbar told me about him. Used to put his hand up their shorts, so Finbar said . .'

'Didn't you report him?' said York.

'No.'

'None of your business, was it?' said York.

He looked accusingly at Patrick.

'I never thought.'

'It's everybody's business – we're always careful with Scoutmasters . '

'But never the scouts themselves?' said Murdoch 'Tommy Bull.'

'You know him?' said Patrick.

'He came before you didn't he' said York 'Is it the same one who was caught dodging his fare on the buses.'

'What do you mean he came before you?' said Patrick.

'I'm a magistrate' said Murdoch 'the case was mentioned in the newspaper – Evening Despatch, so it's in the public domain.'

'In the what?' said Patrick.

'The public domain.' said Murdoch 'which is why I can confirm it. Listen, I'm sure I know where Finbar is, but how he is, I don't know.'

'What happened to the old bus you went off in?' said Carmel.

Nobody answered.

Patrick went to the front of the car and said to York 'Get up – I'm sitting there.'

York got up.

'In fact you may as well go home, if he's where Doug says he is we'll need this seat.'

York started to reply 'Don't you think . . .?

'You lost our son – so you are done here.'

York got out and stood there looking lost.

'Get the forty nine bus, down there or the fifty and you'll be home in no time.'

'And don't forget to pay your fare.' said Murdoch.

'Get hold of Tommy and tell him I want to see him.' called Patrick after York.

As they drove to the top of the hill, to exit New Street Station Carmel said 'I think we should still go to the police.'

'If it'll make you feel better' said Murdoch 'I'll drop you off at Steelhouse Lane – tell them Finbar is missing and we think he is somewhere near Rose Hill, Rednal.'

'Rose Hill, Rednal' repeated Carmel as she got out of the car.

Murdoch and Patrick proceeded along Bristol Road South to The Lickey Hills. Quietly as they both went into a land of thought, trying not to fear what might have happened to Finbar. Patrick trying to relax his rage about Tommy, and he didn't like York's insinuation that he should have reported Tommy when Finbar had told him about what he was doing to the younger boys.

Murdoch had other thoughts: hoping he was right about Finbar, that he would be all right because of his reaction to the tree, and the ambience of the trees, and how a boy who avoided all kinds of education from his school, would have the word divine in his vocabulary.

It might have been a twenty minute drive at that time on that Sunday, but not a word was spoken between them: no talk of how Carmel would be able to explain how her son had been missing for five days without any sign - how could that be explained?

As their thoughts were digested and flown into some kind of osmosis they became as one when they both exclaimed 'I hope he's all right.'

Almost at one just short of a harmony.

Murdoch stopped at a traffic light in Selly Oak and they looked at each other. Not another word out of them and not an expression on either of their faces, but each of them knew what the other was thinking.

Beep – beep!

A blast of a horn from the number sixty one bus and off they went again – silence.

Murdoch pulled in to where he had parked on the day of the picnic. Tommy – he knew who he was, when he was mentioned as it seemed silly for someone who could easily afford it, to avoid paying his fare on the bus. Murdoch always noticed the mode of dress and the air of anybody brought up before him, on the bench, but it was a conundrum to have to be taken to court and be reported in the newspaper for such a paltry sum of money; and now he was driving a sports car – a two seater at the age of just eighteen.

When they crossed over the road, Murdoch stopped just before ascending the hill – 'this is where I believe his bag was found. Away from the road, I should think.'

'Who by?'

'A rag and bone man.' said Murdoch.

'A rag and bone man' said Patrick 'up here up that bloody hill? When was this?'

'This morning' said Murdoch 'at the top of your lane.'

'He found it here and took it all the way to Balsall Heath?'

'I suppose so.'

'On a Sunday morning?' said Patrick 'doesn't smell right to me.'

'I waas getting the car out and he came and asked if I knew South View Terrace.'

Patrick held up Finbar's bag 'Where does is say South View Terrace on the bag – it just says Moseley Scout group.'

Patrick looked around. Then they walked on and after about fifty or sixty yards he stopped. As the grass and bushes parted he saw something shining. He went to it and it was Finbar's harmonica. He picked it up and it was slightly battered as if it had been dropped.

Walking up Rose Hill, was new to Patrick, but Murdoch probably knew every step, and when he came to a slight gap, he went through it and Patrick followed him. They came to the tree, the tree where Finbar had seen the etching and they stopped.

The two men looked toward the tree and Murdoch beckoned forward.

'Finbar' he called.

On the previous Tuesday, after the rain had stopped, Finbar was standing inside the tree, listening out for Tommy – for a moment he thought he heard rustling in some bushes and presumed it was an animal; or was it?

All Hushed.

All Quiet.

Then: ''Finbar?' Tommy's voice.

Again.

'Finbar?'

Was it near, was it far?

He didn't know.

A flash of the torch between the breaks in the trees.

He didn't move.

He tried hard not to breath.

Finbar stood with his back to the bark of the inside of the tree because, even though he was in the hollow of it, there was bark in there. He faced the man on the wall, the plant man or the picture or etching of it, and as it had whiskers it must be a man but there again – the whiskers were of plants and not hair growing from the body – he was standing looking at a delineation of man; neither male or female. All those thoughts and summations accompanied him for an hour and by that time he was sure Tommy had gone.

It was still Tuesday and on that Tuesday, not one morsel of food or drink, had passed his lips, and though he might not have known the word, his electrolytes were craving.

What did Tommy want with him? He suspected he wanted some kind of fiddling or sex and he knew that Tommy knew it wouldn't happen; so what did he want? To silence him?

It was a full moon when he put his head out through the trees and if Tommy had been lurking in the vicinity, he would have heard the churning and turning of Finbar's stomach, or wherever the noise of hunger comes from. He could see bushes with things growing from them, he knew if they were a nasty colour they would be poison; but he needed something. He couldn't feel any moisture from leaves but leaves are leaves and not berries which could be poison, so he pulled a bunch of leaves and, making sure they were not stingers, chewed them which kind of quenched his thirst. He knew they were clean, because of the rain and after a few chews a slight taste ensued.

He knew what magic mushrooms looked like and he knew all the poisonous mushrooms but there were pinkish mushrooms with white spots. He pulled some up and smelled them. Then he licked some of the white spots and they were delicious. Maybe be a bit like sea side rock. Sweet and sticky. He ate a few and it went well with the leaves.

He went back into the tree and the man on the wall was as bright as ever which radiated a glow around the place. As he got near to the circumflex it looked dark inside and when he crossed the threshold the ambience changed and he seemed to be in another world. When he took a step backwards he was outside and the circumflex was dark again.

Back inside, he sat on the shape coming from the tree – it was more like a seat now. The man on the wall had its eyes closed and the next thing Finbar heard was the loud song of a robin – it was morning.

He looked outside and there was a fox lying across the threshold as if on guard. He didn't know anything about foxes and when he stood up the fox got up and walked a few yards away and lay down like any other dog.

Then he noticed the very end of the tail was missing as if . . . he thought of his daddy's chickens and the fox which was caught in the chicken wire; years ago?

Couldn't be. ?

It seemed there was more space outside the tree than he had realised and it was like a clearing in the woods, something like Robin Hood which he had been watching in serial form on the television.

Looking back he saw that the man on the wall had its eyes open. He knew he had slept well but he didn't know for how long as he didn't have a watch. It was August so it could be any time, he was still confused when he heard rustling in one of the bushes so he went back through the circumflex and the fox followed him and lay, again, across the threshold.

The man on the wall had a slight smile on its face and, even though he could easily see it, it looked faded.

More rustling outside.

He ventured closer to the fox to see what was outside – Tommy?

A boy of his age was standing. Not a word from him, not a movement. Finbar didn't know if the boy could see him, as he sneaked a look and, as he didn't seem threatening, or frightening, he stepped outside.

'There you are, Finbar' he said.

This shocked Finbar 'how . . . how do you know my name?'

'I'm Henry.'

It didn't make Finbar move an inch, he looked at him and he had blond hair, like Finbar, but his was much longer: he was about the same age and he was dressed a bit like the characters from long ago – how long ago he didn't know, maybe the time of Robin Hood and he had some kind of flute in his belt and a small holster.

'What are those pictures on your shirt?'

'These?' said Finbar, indicating the scout badges.

'Yes - they're evil.'

'In what way?'

'Many ways' said Henry 'the arrow head is a weapon, that flower is bad. It has the meaning somewhere to obey. To whom?'

'To whom? I don't know.'

'You are wearing badges and you don't know what they mean! One says “duty to god OR scout values” what is that; what is 'or'? Which god?'

'I didn't know that' said Finbar.

Finbar looked at Henry with his oh familiar face, his sun tanned legs, looking something like the boy who was with Tarzan, not wearing shoes but some kind of cloth instead.

'Who are you?'

'You don't know?'

'No.'

Finbar turned away: the fox got up and lay across the circumflex again, this stopped Finbar from going back inside.

He turned back to Henry 'What day is it?'

'Tomorrow' said Henry 'come on, let's go.'

'Where?' said Finbar.

'Time to eat but first we must destroy those evil badges.'

He took the knife from its holster - it fascinated Finbar.

'Offizeirsmesser' said Henry 'an officer's knife in the Swiss army.

'Take your shirt off.'

'Where did you get that?' said Finbar.

'It was here – soldiers were here during the war. It was a high place where they looked out for the enemy. One of the soldiers gave the knife to me.'

'Swiss soldiers?'

'Soldiers with badges – good soldiers, good badges.'

Finbar took off his shirt and Henry, with one of the applications on the knife, started cutting the badges off the shirt and putting them into a pile. Then he scraped dirt from the ground with some little twigs and surrounded the badges: 'There!' he said 'I collected the twigs when I saw it was going to rain.'

He took a piece of flint from his shirt pocket a metal spring looking object from another and, with a piece of black cloth to use as kindling he struck the flint against the metal a few times. Sparks flew from the flint into the twigs and a little glow from one of the sparks started to glow into a flame and burnt the badges.

'What do you think of that?' he said.

'No much' said Finbar 'the scouts taught me how to do it.'

A nice little fire burnt the badges and sticks.

'Do you have a kettle' said Finbar, which made Henry laugh.

'Come on – let's get some food.

No comments:

Post a Comment