I

once met Mrs Gandhi; now if you knew me you would wonder how some bum

of an actor with only one TV credit in the year of 1983 could get to

meet the leader of the world’s largest democracy.

It

had, indeed, started off as a bad year which I had inherited from the

year before; in February I was offered one episode of The

Angels –

a BBC hospital soap – playing the role of a cop in one scene; I

jumped at it; we had three kids to feed.

On

the first day of rehearsals I bumped into a BBC producer, Innes

Lloyd, in the lift at the BBC rehearsal rooms in North Acton –

fondly known as the North Acton Hilton because of its size - and he

told me that he had tried to get me for his John Schlessinger film An

Englishman Abroad,

with Alan Bates, but that my agent had told him I was unavailable.

As

I was a big fan of John Schlessinger’s films, I wasn’t very

pleased; surely we could have come to some arrangement after all I

was only in one scene in ‘The Angels’ and we could have…..oh it

doesn’t bear thinking about.

I

did my one scene – filmed at some hospital in Coventry and started

to look for another agent.

When

I got home one day my wife was buzzing with excitement; I couldn’t

calm her down.

She

had received a telephone call from The Guardian newspaper: our

fourteen year old daughter had won an essay writing competition and

the prize was a couple of weeks in India for two.

The

trip would include staying in New Delhi, Jaipur, Agra, Bombay and

Lonavala staying in the best hotels and included £250 spending money

- each.

The

essay compared life in The Himalayas to life in England; of course

she had never been to The Himalayas and her observations were taken

from her geography lessons and her reading of Victor Zorza’s Indian

columns in The Guardian under the title The

Village Voice –

which was about a village north of New Delhi and not The Himalayas at

all.

I

have to take the credit for pointing out the columns to her and

telling her about the competition.

My

wife was adamant that I should accompany our daughter to India; it

was a world away in those days – it’s a world away these days but

we have seen live cricket from there – and my wife felt our

daughter needed her father; as it happened she was right but that’s

another story.

So

we set off for India: the trip was sponsored by Air India and The

Guardian and judged by the editor of The Guardian, Peter Preston and

my favourite Guardian columnist James Cameron – no not the

Titanic/Avatar creator.

There

were two other winners: a fourteen year old girl from Bristol and a

nineteen year old boy from somewhere in the home counties; his father

accompanied him and the girl from Bristol was accompanied by her

female English teacher.

We

had to have injections for cholera, typhoid and polio and took pills

for malaria.

The

evening before we were due to fly out to New Delhi we met and were

entertained by the Indian High Commissioner and his family at his

London residence; they gave us tea with warm milk and samosas; the

High Commissioner and his family were charming – as it turned out

it was a taste of what was to come – and when they spoke to us they

shook their heads, Peter Sellers style, which was something else we

saw a lot of in India.

Later

that day we were installed in a really nice hotel near Gloucester

Road tube station and went out to eat at a posh Indian Restaurant

close by; ‘Princess Margaret comes here often’ we were told and

we felt really important.

The

following morning we emerged for breakfast and it seemed the father

and son, from the Home Counties, had never eaten Indian food before

and were feeling a bit green around the gills; they hadn’t even

tried it as an experiment when they heard they were going to spend a

little time in the sub-continent; this was also a sign of things to

come: on our second day in India they didn’t even make it out of

their room and had to postpone their trip to the Taj Mahal so we went

ahead without them; I had wondered about the title of the John

Schlessinger film An

Englishman Abroad but

in India it was slowly starting to make sense.

Their

Delhi Belly, or whatever it was, deprived them of one of the greatest

train journeys I have ever taken and the wonderful experience at

Delhi Railway Station; it was such a huge exciting culture shock that

I can still smell and taste it now: everything out of the story and

picture books came to life; porters with four or five suit cases on

their heads, a blind beggar and a beggar with no hands; crowds of

people asleep on the platforms; bikes, rickshaws and more

bikes.

There

was a certain smell about the place; a smell not unpleasant although

it might have been to some; a smell I got to like even though it was

probably a mixture of faeces, urine and spices; the father and son

missed the first class travel on that train, and from New Delhi to

Agra, we were extremely comfortable in individual reclining seats –

I remember thinking ‘you don’t get this in Britain!’

The

food was freshly cooked and the staff on the train was at our beck

and call.

The

lavatories on the train gave an introduction to the Indian way of

life; there were two lavatories in each cubicle: one for the western

way and one for the Asian way; the Asian way was just a hole in the

floor as the Asians squat whilst we, the westerners, sit on the

loo.

As

we looked through the windows on the train we saw plenty of evidence

of this as it was early in the morning and people were going about

their daily ablutions – in public; they were standing under stand

pipes washing their bodies and if we saw one man squatting for a crap

we saw a hundred.

I

still have the image now of men in the distance squatting with a tail

going from their bottoms to the ground.

We

learned that they wiped their arses with the paper in their left

hands and ate with their right.

Our

daughter

had never flown before and the journey from Heathrow to New Delhi was

a good way of getting used to it. I don’t know how long the flight

was but I remember eating, drinking, sleeping, eating again and still

being in the air; the flight wasn’t very full and I appeared in the

‘in flight’ movie on that flight and also on the way back; an

embarrassingly small role, I have to add, and nobody noticed me in

the movie but they all saw my name in the end credits.

Stepping

off the plane the heat and humidity hit our ankles even though it was

April and dark. It was something like five in the morning UK time but

we were raring to go.

We

lived in Northampton at the time – maybe that was why my acting

career was going south – and whenever we told anybody in India

where we lived in England, their eyebrows would lift in confusion and

then they would give that charming shake of the head we had seen at

the High Commissioner’s Residence; they had never heard of

Northampton so we would quickly add ‘sixty miles north of

London.’

Even

though it was late we needed to rise very early the following morning

as an extra trip had been arranged; so at five fifteen I had my first

Indian breakfast: masala omelette, toast and tea with hot milk.

Two

Ambassador type cars picked us up at the front of our hotel and we

were whisked off to Mrs Gandhi’s residence.

Yes

we were going to meet the formidable Mrs ‘G’; her official

residence seemed to be in a residential area, and we were led into a

huge garden; there must have been two or three hundred other people

there as there was some rule in India that anyone could show up to

meet the Prime Minister; whether she actually met any of them I don’t

know.

After

the cold and dark of Britain, we were suddenly in a heat wave and hit

by extreme brightness from the early morning sun; I had my white

jacket on and even wore a tie; the local inhabitants wore very loose

clothes, huge bell-bottom trousers or flairs and nearly all wore

hats.

Parakeets

and monkeys roamed freely as we followed a smiling official towards

the main building; there didn’t seem to be a lot of noise but a

kind of hum about the place accompanied by the whirls of cameras, the

odd call from a human in the distance and then lots of squawking from

the parakeets.

Over

one side of the garden was a party of people huddled together; I got

the impression that this was a whole organisation that had shown up

to see the premier and not just their duly elected

representatives.

We

were shown into a kind of outer room and the others waiting in there

seemed very nervous.

I

suppose as an actor I had worked, and have worked since, with well

known people; well known people in show business world, that is, not

world leaders who go down in history; well known people so full of

themselves, sometimes, that they are very unpleasant and sometimes

when these well known people suddenly become unknown people it’s a

bit of a relief.

After

about five minutes or so we were called and led into another room;

the room didn’t seem to have any aesthetic qualities at all, the

furniture was functional: a sofa, an occasional table and a few

chairs; behind the table was an open French window, which led to a

quiet part of the garden, and another doorway was covered by a

curtain.

When

Mrs Gandhi entered she did the full theatrical bit through that

curtain; she walked in as if she was the leader of the biggest

democracy in the world, she walked in like a world leader, an

important member of the Gandhi-Nehru dynasty and a figure of

history.

She

was accompanied by a few bodyguards; I have often thought about those

body guards as it was her private bodyguard that turned and killed

her eighteen months later in the grounds of that very

building.

Everybody

stood up when she entered and she sat down between the two girls on

the sofa; our daughter and the other fourteen year old girl.

Straight

away it was obvious she was very comfortable with them; she started

to chat informally but I noticed she didn’t have any small talk at

all; she asked them about their essays, how they liked India – even

though we had only been there eight hours - and would they ever

consider coming back again; then she asked them where they lived;

when it was our daughter’s turn she said she lived in Northampton

sixty miles north of London: “I know where Northampton is” Mrs

Gandhi snapped “I was at Oxford.”

At

one point I noticed Mrs Gandhi ring a bell she had secreted in her

hand; through the curtain came somebody and before we could see them

she asked them to get a photographer; this was the cue for us to

stand behind her but it was also the cue for the bodyguards to push

and shove each other to try and get into the shot.

I

was standing at the end so didn’t think I had a chance of being

included because when the photographer got ready to take the photo he

seemed to aim it over to the other side of the room; but one of the

body guards tried to get his face in to the shot and gave me a little

push; I shoved gently back and in the subsequent photo he disappeared

totally behind the person standing next to me; serves him right.

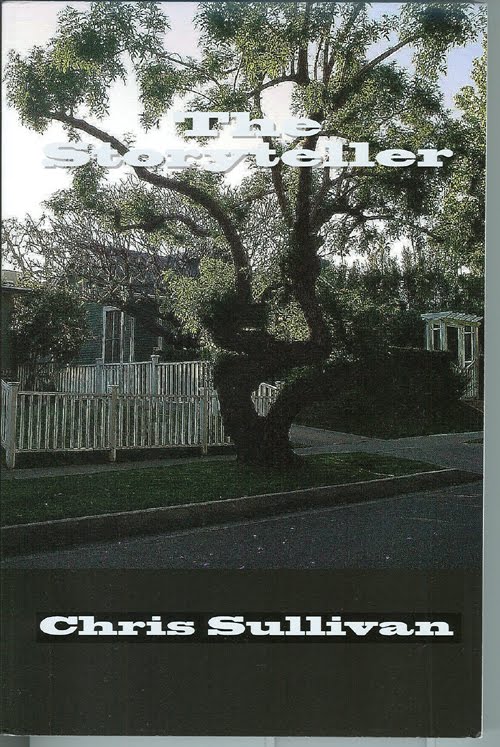

See above.

After

the photo Mrs Gandhi shook hands with a couple of us and swept out as

sweepingly as she had swept in.

I

often think about those body guards.