Every

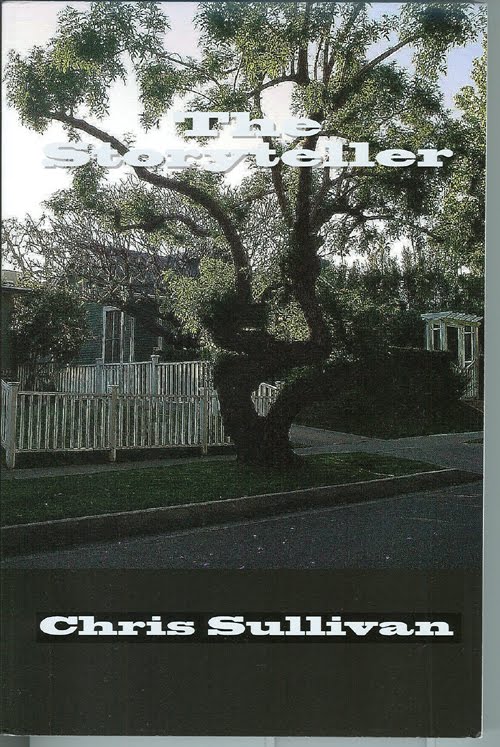

Saturday morning, Sam Norton would leave his flat, near Pinner Green,

and go to the superstore just around the corner; well round the

corner and up the road; a very busy road, even though it wasn't a

main thoroughfare; but it had traffic lights, a little island and a kind of

slip road to the store. On the left hand side there was another

little street which led to a block of council flats, a halfway house

for ne'er-do-wells and some kind of shelter.

The

Jewish delicatessen, on the other side of the street, was a mystery

to Sam as it always seemed to be closed. Sam ventured in there one

day, as he loved all kinds of Jewish food, but found their bill of

fare offered little more than pre-packed produce from big chain

suppliers.

Sam's

mission, on Saturday mornings, was to buy a lottery ticket. He would

use the same numbers every week which were, 1, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 29.

He knew that if he ever won the jackpot he would have to share it

with many others as they must be popular numbers; but there again,

other people might be like him and know

that they were popular numbers and not choose them and there again,

he was sure his double bluff would mean he might be the only winner

after all.

Sam

knew the numbers by heart but, every Saturday, he would give the

clerk at the lotto desk a MyLuckyNumbers

card with a bar code, which would automatically print the numbers on

the lottery ticket.

That

was the way he liked to do it as he thought it would bring him luck;

he knew too that if he changed his numbers one week they would come

up the following week.

His wife would know the numbers in any

case as number 1 was his birthday, number 7 his wife's, 14, 21

and 28 were the birthdays of their three children and they were

married on the 29th.

One

Friday evening, when coming back on the Tube train from Baker Street,

he noticed that The

Evening Standard

had not been delivered to the supermarket by the station so after a

beer, and looking at the latest news on the television, he went out

to the superstore around the corner to pick up a copy of the

newspaper.

As

he walked away from his building, the light rain hit him in the face;

it didn't seem to be coming down heavily so he carried on walking for

a while but then had second thoughts so he called his wife and asked

her to throw down his hat.

This

she did and when he caught it she suggested that he might buy the

lottery ticket to save going the next day.

'No'

he said 'I don't want you throwing down the card; it'll blow away.'

'You

know the numbers' she said 'just fill them in.'

From

the brief description above, you will know that that wasn't Sam; he

would only buy his lottery ticket with the little card he used every week; he even kept a copy of how many times he had done the

lottery, how much each ticket cost annually and kept it in his little

drawer; he never thought to multiply the number of weeks in the year

with how much each ticket cost.

So

with his hat on, his ratting hat, as he called it, he wandered up to

the traffic lights on Pinner Green, went around the corner and, as

soon as he was passed the road restrictions of the traffic lights, he

saw a man lurking around a parked car.

He looked a bit suspicious,

although Sam couldn't figure out why, but why was he messing with the

lock? Also the man reacted when he saw Sam.

As

Sam walked passed, matey boy walked behind him and as he walked, Sam

slowed down to let the geezer overtake him. But he wouldn't pull

away. He kept looking at Sam. When they were about to pass the

fish'n'chip shop Sam suddenly walked in. The place was empty and the

woman, who owned it, came out from the back to serve Sam.

'I

just thought I'd come in and say hello' he said 'I've been away!'

'How

nice' the woman said 'how are you?'

'I'm

fine' said Sam 'I'll see you soon.' and he left.

He

could see on the slip road, about one hundred yards ahead, the man,

standing looking at the people passing.

Sam

didn't look at him as he passed. He was going to pick up The Standard

and go straight back home but decided to walk around the store first

to give the man a chance to disappear.

On

the way back there was nobody on the street; nobody at all. The man

had gone and Sam walked back to Pinner Green.

It

must have been about 10.00 pm when the police knocked Sam's apartment

door. His wife had fallen asleep in front of the television and the

knocking gave her a start.

She

didn't know the time and as she went to the front door she called

'Where's your key?'

But

it was the police she saw as she opened it.

The

woman from the fish'n'chip shop had identified Sam when the police

came in to her 'chippy' – identified his body by his clothes, more

than anything else, especially his 'ratting hat.'

She

told the police which apartment Sam lived in but she never knew his

name.

The

police weren't sure as Sam had no I.D. and it took a lot of

organising and diplomacy to ascertain that Sam lived with the woman

who had answered the door and in fact she was his wife.

There

were no witnesses to the murder and it took a lot of red

tape

and extensive permissions before Sam's body was even released.

The

television company called her one day, in conjunction with the

police, to see if she would take part in a reconstruction programme

called Crimewatch;

she

didn't want to have anything to do with it as she thought it would

upset her.

So they filmed the

programme without her but she was right about being upset especially

when she saw the actor who was to act as Sam; he even wore Sam's

ratting hat.

As she watched she

saw the reconstruction and it showed CCTV of Sam going to the Lottery

Counter to buy his ticket.

As

far as she knew Sam didn't buy a ticket. There was nothing on him at

all, the murderer had taken his wallet and even The

Evening Standard.

She couldn't

remember the lottery ticket for the week Sam died and, in fact, she

hadn't even looked at the lottery since. She was with their eldest

son and he wondered where the ticket was – maybe it was a winner.

There is a web page

with all the results and their son looked on line to see if there had

been a winner with Sam's number and sure enough he found the numbers

1, 7, 14, 21, 28 and 29 four weeks after his father had died and Sam

had been right all along – there were seventeen winners.

The rest was easy – Sam's DNA was on one of the people who had claimed the prize; he lived in Wembley - or he did before they locked him up.